Septiembre 15 y 16 y 17 de 2008

European Parliament

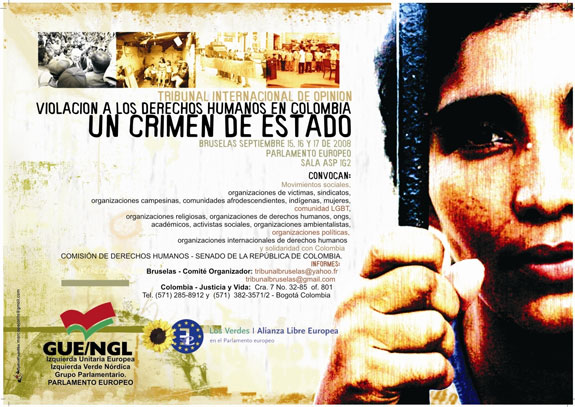

BRUSSELS DECLARATION CONCERNING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN COLOMBIA

The International Opinion Tribunal convened in the European Parliament, in Brussels, on September 15, 16, and 17, 2008. Having taken notice of the verdicts of seven sessions between 2002 and 2008 of various opinion tribunals concerning Colombia, and upon hearing the testimony of more than twenty witnesses from various social movements and human rights organizations and reviewing voluminous documentation, the Tribunal concluded that the allegations before it of State crimes had been substantiated.

The International Jury was composed of François Houtart of Belgium (president), Carmencita Karagdag of the Philippines, Ulrich Duchrow of Germany, Patricia Dahl of the USA, Mierille Fanon-Mendez of France, Moira Gracey of Canada, Carlos Gaviria of Colombia and J. Luis Nieto of Spain.

The allegations and evidence were compiled by a group of Colombian victims’ organizations, unions, small farmer movements, Afro Colombian communities, indigenous peoples, human rights organizations, sexual minorities, religious organizations and international solidarity organizations, and by the office of the President of the Human Rights Commission of the Colombian national Senate.

THE FACTUAL BASIS FOR THE DECLARATION

The documentation received by the Tribunal was as follows:

-

Judgment of the Permanent People’s Tribunal;

-

Paper concerning extra-judicial executions;

-

Report of the verdict of the hearing concerning indigenous people;

-

Video of the hearing in Buenaventura concerning the Afro Colombian population;

-

Video concerning mining in Norte del Cauca;

-

Video concerning displacement of Afro Colombians in Olai Herrera;

-

Report concerning the Colombian Pacific: The Naya case;

-

The Afro Colombian population between war and hate;

-

Report of the Coalition of Movements and social organizations concerning the Right to freedom of expression, opinion and association in Colombia;

-

Verdict of the Tribunal concerning Sur de Bolivar;

-

Video concerning the eviction of families in Bogota neighbourhoods for failure ot pay bank loans;

-

Report concerning State discrimination and/or indifference presented to the Senate of the Republic;

-

Report on Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Arauca;

-

Book concerning Human Rights of lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transsexuals in Colombia

-

Verdict of the tribunal concerning forced displacement;

-

Report by Fensuagro-CUT concerning the human rights situation and violations;

-

Video of massacres and human rights violations in Buenaventura;

-

Syntheses of the accusations put before various Opinion Tribunal in the last two years;

-

Verdict of the International Opinion Tribunal concerning forced displacement in Colombia and annexes of women’s cases;

-

Recent cases of assassinations, recruitment and disappearances in Ciudad Bolivar;

-

Cases presented to the International Opinion Tribunal concerning forced disappearance.

-

Cases presented to the International Opinion Tribunal concerning forced displacement.

The witnesses and the issues concerning which they gave evidence were as follows:

-

Human Rights in Colombia, by Senator Alexander Lopez;

-

Conclusions and future challenges of the Permanent Peoples Tribunal, by Gianni Tognoni;

-

Situation of indigenous peoples generally and the Kankuamo people in particular, by Gilberto Arlant;

-

Extrajudicial executions and mechanisms of impunity by Byron Gongora Arango;

-

Policies of displacement, discrimination and repression against the Afro Colombian population, by Jose Santos Caicedo Cabezas;

-

Intimidation, persecution and assassination of social leaders and the disintegration of social organizations, by Omar Fernandez;

-

Violations of human rights in Bellacruz – Sur del Cesar, by Ariel Toscano and Darlin Narvaez;

-

Violations of human rights in Sur de Bolivar, by Efrain Muñeton;

-

Victims of the financial sector, by Juan Rodríguez;

-

Violations of gender identity and sexual orientation, by Robinson Sanchez;

-

Mass detentions in Arauca, by Sonia Lopez;

-

Extermination of the small farmer movement, by Eberto Diaz;

-

Massacres and human rights violations in Buenaventura, by Winston Barahona;

-

Summary of the accusations brought before the Opinion Tribunals in Colombia in the last two years, by Lilia Solano;

-

Assassinations of union activists, by Amanda Rincón, Diego Alonso Arias y Oscar Figueroa.

The Colombian ambassador in Brussels, Mr. Carlos Holmes Trujillo was invited to appear before the Tribunal to provide the perspective of the Government of Colombia concerning the human rights situation there. While he received the invitation and the Tribunal scheduled a time of 2:30 pm on September 16, he chose not to attend.

-

The social-political context of human rights violations in Colombia

Since independence, Colombia has been characterized by a social dichotomy: monopolization of economic, political and cultural power by an essentially urban minority on the one hand, and on the other hand, the vast rural masses living a subsistence existence. The social injustice that has reigned since the colonial period deepened during the neoliberal period. According to a 2007 report of the UN Development Program, 17 million Colombians live in poverty, and six million in extreme poverty, who live on less than one dollar a day and the gap between rich and poor continues to widen.

Colombia has one of the most unequal distributions of wealth in Latin American, despite being a rich country with annual economic growth of 7%. The neoliberal logic that promotes spectacular growth for some 20% of the population applies perfectly to Colombia country. Only 0.3% of the population owns more than half of arable lands in the country.

Politically, two parties – Liberal and Conservative – have controlled Colombia since the nineteenth century, alternating more or less regularly between the two, and occasionally governing by mutual pact (a period known as the National Front). These parties both represent the interests of the business class or bourgeoisie and large landholders, and they have never permitted the expression of a political alternative. Every time a political leader has appeared on the scene that appeared to have some hope of motivating real change, he has been assassinated or died violently: Jorge Eliecer Gaitán, Camilo Torres, and more recently Jaime Pardo Leal, Carlos Guillermo León Gomez and Bernardo Jaramillo.

Attempts by opposition groups to abandon armed struggle and enter the political arena, for example M-19, have been hindered by assassinations of their leaders and members. The clearest example of this rejection of any political alternative is the physical elimination of more than 3000 members of the Patriotic Union (which has been called a political genocide).

Social injustice, the tight monopoly on political power, and the impossibility of real alternatives through democratic means, among other factors, explain the rise of armed insurgent movements in the early 70s, after a civil war between Liberals and Conservatives resulting from the assassination of Gaitán, known as “the violence”, which took the lives of 300,000 people.

Since the 1970s, drug trafficking has become an integral part of many social and economic structures of the country, such that it is now part of Colombia’s political and economic reality. Major drug cartels were organized, and proceeds of the drug trade penetrated the entire economy. Drug money is laundered through the financial system, construction work, and almost every sector of the economy. It has also penetrated the political system and society generally: the armed forces, parliament, courts and government.

Over a 40 year conflict, the methods employed by the guerrilla have degraded to the point of taxing drug sales, and civilian retention.

Since the 1970s, even prior to the appearance of guerrilla movements, a U.S. military mission forced Colombian governments to broaden the paramilitary strategy (already being used by large landowners) to confront dissident ideologies through progressive legalization of their activities. This strategy peaked in the 1980s and 1990s and continues today. Paramilitary groups have grown to the point that they control entire territories, and have used the most reprehensive repression methods against the civilian population: indiscriminate and targeted collective massacres; forced disappearance and torture, forced displacement, rape, and the appropriation of the lands of small farmers, black communities and indigenous peoples.

From the beginning of the armed conflict, assistance from the United States has consistently increased, most recently with the so-called war on drugs, and since 1998 has been organized under the name “Plan Colombia”. Plan Colombia rapidly became a counterinsurgency strategy. The “Patriot Plan” and its consolidation with “Plan Colombia” pursue the same objectives, in a country of geopolitical strategic importance for the empire of the North.

With the election of President Alvaro Uribe Velez in 2002, the conflict expanded to involve a significant swathe of civil society through his so-called “democratic security” policy. The explicit goal of this policy is a military solution to the conflict. From the beginning, it developed methods and policies that implicate the civilian population in the war through informant networks, small farmer soldiers, etc.

Since 2004, the government has initiated a process to demobilize paramilitary groups. It soon becomes clear that the various legislative measures enacted as part of this process were in fact a covert amnesty to ensure impunity for paramilitary members. Although several of its provisions were held to be unconstitutional, Law 975 of July 25, 2005, named “Justice and Peace” permits major paramilitary leaders to escape punishment for serious crimes. In addition, impunity has been provided for 14 leaders of the AUC (Colombia United Self-Defence, who was extradited on May 13, 2008, and thus evaded responsibility in Colombia to the numerous victims of their crimes.

Although the government denies complicity with paramilitary groups through both civil and military state apparatus, such complicity has been demonstrated by the Courts, which are currently investigating dozens of parliamentarians from the governing party, including the cousin of the president of the Republic himself, for collaborating with paramilitary organizations. Thirty seven parliamentarians are currently imprisoned for such actions. Of the two possible options available to the government – negotiate with the insurgency and confront the paramilitary; or deepen the war against the insurgency and ally itself with the paramilitary – this government has clearly chosen the latter.

What appears to be a political system at the service of societal elites and international economic interests using democratic forms and institutions, in fact operates very differently, engaging in a ruthless campaign against popular social movements and human rights organizations and systematic assassination of community and labour leaders.

The most recent example of this policy is president Uribe’s reponse to the strike by sugar workers in Valle de Cauca that began the first day of the Tribunal. These workers seek better work conditions and oppose the expansion of cane fields for bio-fuels at the expense of biodiversity and food production. The president pronounced:

We must suffocate the cane cutters’ riot in Valle; use all possible force, do not curtail its repression, if needed, mobilize all the soldiers in the country.”

Colombia’s current leadership subscribes to a model of harsh domination, and in this it is supported economically by multinational corporations, including some from Europe, and militarily by the United States, with the tolerance or assistance of European institutions.

-

Testimony before the Tribunal

Thirteen of the witnesses before the Tribunal come from the most vulnerable sectors, which are most affected by the violence of Colombian political society. They testified about numerous crimes: extra-judicial executions, disappearances, massacres, torture, forced displacement, arbitrary arrests and detentions, all with utter impunity – impunity institutionalised in practice and literally written into the legal system.

Engaging in this behaviour and denying its existence is a crime in itself. The Justice and Peace Law, which offer immunity in exchange for a confession, in mixing illegally acquired assets and the demobilization, works in fact to reinforce the paramilitary network while creating an appearance of justice. As one witness said, “Every time we denounce these acts to judicial bodies, things get worse.” Another said “They came before with boots and uniforms; now they are in public office.”

We are reminded that the practice of using paramilitaries was used in Europe in the twentieth century, when governments such as Nazi Germany with the Freikorps, fascist Italy with the black shirts and Great Britain with the Black y Tans, organized cooperation between their military and high level politicians and those groups. They acted against all those accused of being unpatriotic or communist, and of workers who organized to vindicate their rights.

In Colombia, impunity exists from the national level down to the local level. Investigations are not undertaken at the scene of the crime. Several members of social movements that collect information concerning massacres, disappearances and displaced people affirmed that not a single of those cases had resulted in a conviction, and very few were even brought before the courts.

Former members of the Senate Human Rights Commission are currently incarcerated for ties with paramilitary groups.

According to the evidence, in Colombia local and international investment relies on paramilitary forces to secure its interests, and to appropriate lands. In the words of a witness, “Without land we are nothing. We do not want to be slaves for a salary in the city.”

The lack of agrarian reform preserves a situation in which 15,000 people own more than 49 million hectares, while more than 1.5 million families own no land at all. This has resulted in the dispossession of indigenous and Afro Colombian communities.

Indigenous and Afro Colombian communities are vulnerable because they occupy resource-rich territories, a richness that has become, in the words of one witness “a burden and a curse.” In a witness’ words, “Our land is our life; our life is our land.”

Colombia’s indigenous peoples continue to fight to keep their lands. When Uribe declared that racism and discrimination do not exist in Colombia, community leaders brought a proposal to the Senate regarding discriminatory practices. Repeatedly, the proposal was rejected. The government logic was that the proposal was unnecessary, since in their eyes there is no discrimination or racism. “They treat us as valueless; that way, they can eliminate us if they want to”.

As has been the historic experience in other countries with paramilitary groups, Colombian armed forces receive training in foreign military institutions to vilify any group that challenges elite control. Those who organize themselves to seek change to their situation are labelled guerrilla collaborators or members, which set the stage for justifying atrocities committed against them. Repeatedly, after they are killed their identities are obscured in order to present them as fallen guerrillas, and they are displayed with firearms on or near their bodies to justify the assertion that they died in combat. Other people who challenge the established social order in different ways are also singled out, even though they do not organize politically. Small businesspeople and travelling vendors are attacked and disappeared. Homeless people are forced to pay protection fees. Sexual minorities are clearly targeted of threats and attacks.

Teachers, whose union organization is strong and vocal, are repressed and live in fear of extra-judicial executions,. Paramilitary groups approach administrators and prohibit them from supporting any resistance. Assassinations of Colombian Federation of Educators’ members thus far in 2007 already exceed the number suffered in the entire year of 2007. “The want to break the teachers’ spine.”

Arauca, a region with large oil deposits located on the border with Venezuela, is subject to the full range of abuses. The year 2007 saw the highest number of violations in recent decades. Fumigation (pesticide spraying) has increased on the pretext of eliminating coca, despite the fact that communities proposed eradicating coca crops by hand in exchange for sufficient infrastructure to enable legal crops to get to market. The state refused.

Militarization of daily life has become the norm in Arauca. Meetings of students, communities, workers, even parents are disrupted by military personnel who take photos of participants. Security forces carry out programs in the school in which students are dressed in military uniforms as “soldiers for a day”. Relatives of social leaders are photographed and their information delivered to intelligence services. An example heard by the Tribunal was that of a social gathering, a party, into which security forces forced entry, yelling “Who is guilty?” – a reference to the guerrilla. They arrested 93 people, handcuffed them and took them to the barracks of the 18th Brigade. Of that group, 43 were accused of various crimes and being guerrilla members. They were jailed for 15 months before being release. As one witness said, “It is one thing to come here a talk about these things; it’s another to go back and live it. I will return to hear about another massacre.”

Victims of the financial sector gave evidence that Colombia is the only country in the world where residential housing mortgages earn such exorbitant interest rates that they provoke financial ruin, eviction and breaking up of families and high numbers of suicides by debtors.

Despite all this, social, labour and community organizations continue to struggle to build a dignified life. Human rights have come to represent first, the right to life, and then the economic rights to food and housing, health and education. In some parts of Colombia, people fight for another right as well: the right to life free from the chains of a parasitic economic mode of productions. In the words of a victim, “Without the land, we are nothing. We don’t want to be slaves in the cities for a salary.”

-

Synthesis of Previous Verdicts.

a. Verdicts

The Tribunal received verdicts from four previous Opinion Tribunals held in recent years concerning different aspects of the human rights situation in Colombia:

-

Verdict of the International Opinion Tribunal of November 29, 2003 (Paris), concerning Impunity (South Bolivar case);

-

Verdict of the International Opinion Tribunal of November 23, 2007 (Bogotá), concerning Forcible Displacement;

-

Verdict of the International Opinion Tribunal of April 26, 2008 (Bogotá), concerning Forced Disappearances, a State Crime;

-

Judgment of the Permanent Peoples Tribunal of July 23, 2008 (Bogotá), and its three preparatory hearings, concerning Transnational Corporations and the Rights of Peoples in Colombia, 2006-2008.

These verdicts are attached to this Declaration. They are all the result of extensive processes of assembling documentation and hearing viva voce testimony from numerous experts and victims. Each tribunal was preceded by various regional hearings, in which victims and social organizations provided testimony and evidence.

b. Factual findings of the Tribunals

The facts and information presented to all the tribunals highlight the alarming situation that Colombians continue to experience. All the tribunals were informed of a litany of human rights violations: assassinations, disappearances, torture, threats, detentions, crop destruction, and forced displacement. All of these are carried out with the complicity or virtually complete incapacity of the judicial system to provide either protection or remedy for these events. This latter situation indicates a consistent environment of impunity for those responsible for human rights violations.

Some facts serve to illustrate the situation: more than four million Colombians have been internally displaced; an even larger number have fled the country. The mechanisms of displacement and dispossession include herbicide spraying (even in regions with no coca), indiscriminate bombing, assassinations and harassment by paramilitary forces, and mass arrests. Furthermore, between 2002 y 2007, at least 955 cases of extra judicial executions committed by official military forces were documented. In almost the same period, 11,292 people were killed or disappeared. In the last 30 years, at least 30,000 people were disappeared alone.

The Colombian State’s Responsibility

All of the verdicts underline the Colombian state’s responsibility in the vast majority of violations in evidence before them, committed either directly by military personnel, police forces or other state officials, or by state-created and sponsored paramilitary forces. The nexus between the paramilitary groups and the State has been clearly established in all the verdicts, which refer to indicators including the 1968 legislation that permitted their creation, their use of military equipment and vehicles in paramilitary operations, and the direct involvement of soldiers in these groups.

The verdicts agree that an almost complete situation of impunity continues to exist for the authors of human rights violations in Colombia, echoing the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’ comment that:

Human rights monitors judge that virtually 100% of all crimes that involve violations of human rights go unpunished. The Commission’s experience … substantially supports that assertion. The Commission is aware of very few cases in which the State agents responsible for human rights violations have been criminally sentenced.

This impunity survives intact despite recent legislative measures supposedly designed to reduce it. For example, after four failed bills attempting to define forcible disappearance as a crime, Law 589 of 2000 was enacted criminalizing forced disappearance, torture, and genocide. Nevertheless, seven years later, not a single charge has been laid, much less a conviction obtained, under that legislation.

In 2003, the national government enacted legislation to reintegrate paramilitary members into society, laws that in effect reinforce and institutionalise their impunity. Law 782 of 2002 benefited more than 35,000 low-level paramilitary operatives who, upon registering under it, would be immune from criminal charges, and made eligible for monthly support payments, business financing, and preferential treatment in hiring and academic institutions. Furthermore, under Law 975 de 2005 (labelled the “Justice and Peace Law”), sentences for paramilitary members against whom criminal proceedings were already underway in the ordinary justice system for crimes against humanity, were limited to between 4 and 8 years imprisonment. Under ordinary criminal law, these crimes are punishable with up to 45 years in jail. In this context, paramilitary leaders have come forward and freely confessed to committing thousands of selective, systematic mass atrocities including forced disappearances, torture, dismemberment, extra judicial executions, and drug trafficking.

The Logic of Repression

Lastly, all the verdicts concluded that the State, paramilitary groups, and multinational corporations derive direct economic or political benefit from the consequences of these human rights violations, rendering unconvincing the portrayal of these violations as mere side effects of the armed conflict. Political benefit from these violations comes in the form of weakened political opposition due to fear and insecurity created within social movements; and more directly in the direct agreements between politicians and paramilitary groups to coerce constituents to vote in their favour.

The verdict in the South Bolivar case concluded that multiple cases of assassinations, massacres, forced disappearances and other violations were committed in order to facilitate a transfer of ownership of area resources, particularly gold deposits.

Forced displacement resulting from the expulsion of populations from large areas of the country, particularly indigenous, Afro Colombian and peasant farmer communities, has created one of the larges humanitarian crises in the country. Nevertheless, the government denies the existence of this phenomenon altogether. The verdict of the tribunal concerning forced displacement highlighted that evictions of urban neighbourhoods, communities and even entire indigenous peoples are do not only result directly or indirectly from the armed conflict, but are concentrated in economically or strategically valuable regions and serve national and international economic interests in agricultural, industrial, mining, tourist, and transportation projects. In this sense, today’s forced displacement continues a process begun with the Spanish conquest, and has served to facilitate extreme concentration of the best lands in very few hands. Additionally, the tribunal concluded that forced displacement serves to ‘recapture’ areas where residents are socially and politically organized in opposition to government plans.

Similarly, the verdict concerning forced disappearances noted significant changes in that activity. No longer are the victims solely political opponents (as has historically been the case, resulting in obvious political benefits), but now also include groups considered to be “social garbage”: homeless people, prostitutes, drug addicts, homosexuals and Afro Colombians; that is, people considered unproductive in the dominant economic model.

The dramatic growth in foreign investment in Colombia is described in the verdict of the tribunal concerning transnational corporations: between 1990 and 1997 foreign investment increased by 1,300%; and between 2000 and 2005 it grew another 168%. Given that economic theory posits that investment flees from instability and legal vacuums, this statistic supports the observation that violence and human rights violations in Colombia serve the interests of large companies. In fact, the tribunals were made aware of situations in which multinational corporations directly contract or finance paramilitary groups.

The tribunal concerning transnational corporations provided a new element to the analysis of Colombia’s complex conflict, evaluating the role played by the international community in the development of the conflict, the interests at play, and their behaviour. It particularly noted the role of transnational corporations with a presence in Colombia in the conflict, and their involvement in practices that violate human rights. Among such Corporation are following European companies: Nestlé, Holcim, Glencore-Xtrata, Anglo American, Smurfit Kapa – Cartón de Colombia, British Petroleum, Repsol YPF, Unión FENOSA, Endesa, Aguas de Barcelona, Telefónica, Canal Isabel II, Brisa S.A., Banco BBVA y Banco Santander.

Finally, all the tribunals held the Colombian state responsible not only for human rights violations but for crimes against humanity, including: murder, extra judicial executions, extermination, genocide, forced displacement, deprivation of freedom, political and racial persecution, torture and forced disappearance, all in the context of a widespread and systematic attack directed against civilian populations. All the verdicts articulated strong condemnations of the situation of impunity maintained by the Colombian state, the effects of the destruction of the social fabric, growing impoverishment and deepening inequality, all of which complete an overall picture of total absence of democracy.

5. Legal Basis for the Declaration

The legal basis for the Tribunal’s conclusions rest on various sources of law. Firstly, the 1991 Constitution of Colombia increased the catalogue of human rights derived from the concept of human dignity, and made respect for such rights a path to peace, since the constituent assembly’s theory was that deterioration in the former is related to the lack of that good (peace) to which the Constitution itself assigns the scope of law (art.22).

The Constitution prohibits the suspension of obligations accepted by Colombia through human rights treaties or conventions, even during states of emergency, asserting they retain the same unconditional authority as constitutional norms themselves, thus giving international commitments the same unassailability as internal legal principals.

From whatever perspective this issue is viewed, it is clear that meaningful application of human rights was a priority for the constituent assembly, which prohibited State institutions from suspending or evading those norms under any circumstances, and made international commitments and internal norms in the so-called constitutionality block a doctrinal and jurisprudential norm solidly grounded in article 19 of the Constitution. An exasperating paradox is that these same principals and norms that bind the state require state action to protect them. In a state of crisis such as that experienced by Colombia for more than half a century – and which the 1991 constituent assembly sought to overcome – it must be underscored that there must be an end the current state of disinformation by the state and its paramilitary children, which itself is also part of that crisis that the 1991 constituent assembly considered to be of the highest order.

Below is a list, though not exhaustive, of the major international legal instruments and internal legal provisions that contain these human rights.

a. Constitutional Law

According to Article 1 of the Constitution, the Colombian nation is founded upon “respect for human dignity, labour and solidarity among its peoples and the supremacy of the common good.” It includes “peaceful coexistence and just order” as essential objectives of the state, and instructs authorities of the Republic “to protect all persons resident in Colombia; their life, honour, property, beliefs and other rights and freedoms.”

The Constitution then promptly proclaims those fundamental rights that the State must guarantee, respect and enforce respect for: life, personal integrity, equality, legal personhood, honour and privacy and reputation, free personal development, freedom from slavery, freedom of conscience, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, right to honour, right to peace, right of petition, freedom of movement and residence, right to work, freedom to choose a profession or occupation, academic freedom, personal freedom, due process, freedom of association and unionisation.

The Constitution also enshrines a series of economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to education, health, decent housing, social security, family, special rights of children, right to ones own culture, rural workers’ rights to land ownership, etc.

b. International human rights norms and international humanitarian law signed and ratified by Colombia

The State of Colombia has made a commitment not only to the people of the nation, but also to the international community through various international human rights and humanitarian law instruments, to guarantee and respect these norms.

International Human Rights Law

-

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly Resolution 217 A (III) of December 10, 1948;

-

American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, approved by the Ninth International Conference of American States (Bogotá, Colombia, 1948);

-

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, entered into force for Colombia on March 23, 1976 through Law 74 of 1968;

-

American Convention on Human Rights, entered into force for Colombia on July 18, 1978 through Law 16 of 1972;

-

Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, entered into force for Colombia on January 8, 1988;

-

Convention on the Rights of the Child, signed and ratified by Colombia in 1991;

-

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, entered into force January 12, 1951;

-

United Nations, Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, which, while not an international instrument capable of adhesion or ratification by Colombia, has been tacitly and directly incorporated into its legal framework through Law 387 of 1997.

These international instruments contain the following rights: life, personal liberty, security of the person, physical integrity, legal personality, due process, judicial protection, privacy, honour, freedom of movement, freedom of thought, conscience, opinion and expression, unionisation, family, privacy in the home, humane and dignified treatment, right to a name.

c. International Humanitarian Law

-

Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, signed and ratified by Colombia in 1961;

-

Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, relative to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, ratified by Colombia in 1996;

-

Article 3, common to the four Geneva Conventions.

These instruments protect and guarantee security, physical integrity and freedoms of civilians not involved in armed conflicts within countries, and of combatants who for any reason have not participated in combat.

d. Internal Legal Norms

The Colombian state, under pressure from the international community and broad sectors of the victimized population, has enacted legislation concerning the violation of these fundamental rights. Law 387 de 1997 designates public policy concerning attention for forcibly displaced populations; Law 589 of 2000 includes (for the first time) forced disappearance, torture, genocide and forced displacement in the Colombian Criminal Code.

The government is also constitutionally obligated to respect the autonomous law of Colombia’s indigenous peoples.

The facts presented to the Tribunal contradict national and international law and thus attract and deserve strong condemnation.

6. EUROPEAN RESPONSABILITY

Since 2002, large European corporations have demonstrated increased interest in Colombia. A pacification strategy was developed and supported by the United States, financial groups and European business sectors. The European Commission and Council Europe support the “peace process” both politically and financially, including the Justice and Peace law.

Despite the fact that the Colombian government is responsible for systematic violations of human rights and crimes against humanity, support from various European Community states, and others such as Switzerland, make them complicit in those violations. The following are some concrete ways in which this responsibility is incurred:

European multinacional Corporation (Unión FENOSA, Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, Banco Santander Central Hispano, Endesa, Prisa, Aguas de Barcelona, CEPSA, Gas Natural, de España, BP y Nestlé de Suiza) are implícate in:

-

The forced displacement of populations by the armed forces, police and particularly paramilitary groups, in order to control territory for monocropping, mining activity, oil extraction or the tourist industry. As examples we can name Repsol (Spain) and BP (Great Britain);

-

Violating ILO Convention No. 169 with regard to respect for indigenous peoples’ natural resources (BP – Great Britain);

-

Denying workers’ rights, as in the case of Nestlé (Switzerland) y BBVA (Spain);

-

Using paramilitary groups as private security for their companies. And example is BP;

-

Pressuring local politicians not to intervine;

-

Investing in communications media that portray Colombia as a democratic company, as in the case of the Spanish group Prisa;

-

Financing projects with disastrous environmental and social impacts, as in the case of Banco Santander (Spain), among others.

-

The European Union mandates use of biofuels (20% renewable energy by 2020), which creates incentive to expand sugar cane monocropping (ethanol) and oil palm (agrodiesel).

-

The European Investment Bank (EIB), the largest international public financial institution in the world, provides financing to multinational corporations in Colombia, without sufficient conditions concerning environmental norms and basic conditions of respect for human rights.

-

Bilateral treaties between European countries and Colombia: here we are speaking of Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania.

-

Agreements under the framework of the Andean General System of Preferences (SPG), which gives preferential status to Colombian exports to Europe.

-

Negotiations toward a Free Trade Agreement, without any serious questioning of the human rights situation.

-

Military cooperation between Colombia and the United Kingdom, and between Colombia and France, and the sale of arms to Colombia by various European countries, including Spain and Belgium.

We call on European economic and political actors to:

-

Renegotiate all agreements with Colombian on the basis of Article 2 of the Association Agreement, which stipulates that an agreement may be annulled if one of the parties violates human rights;

-

That the EIB apply the same criteria;

-

Termination of all negotiations with the objective of privatisation or liberalization measures that benefit European transnational companies rather than the people of Colombia;

-

An end to energy policies that stimulate biofuel production in Colombia;

-

Financial support for social programs that benefit populations most in need, in partnership with popular social movements;

-

Contribution to compensation for damage resulting from European economic policies;

-

Support for social organizations and movements that struggle for human rights in Colombia, and in particular for their efforts to present their cases to the International Criminal Court;

-

Active cooperation with the peace and reconciliation process, which honours the need to reconstruct memory, commence political negotiations, and establishing economic and social structures that guarantee justice, truth, compensation for victims and prevent repetition of these crimes;

-

Suspension of financial support to development projects that strengthen paramilitary groups and the politicians involved with those groups;

-

Condemnation of the Justice and Peace law and the National Reconciliation and Reparations Commission as inadequate judicial and political instruments to address the claims of victims of human rights organizations, and support for a true process of truth, justice and compensation;

-

Suspension of all military agreements and the sale of arms or military equipment of any type by European Union countries to the government of Colombia.

-

Nullification of the Directive approved by the European Parliament regarding the return of immigrant population, among who are the Colombian population.

CONCLUSION:

Having considered both the results of various previous tribunals and heard direct evidence ourselves, this Tribunal confirms the verdicts of the previous International Opinion Tribunals and DECLARES: THE GOVERNMENT OF COLOMBIA IS GUILTY OF CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY. The Tribunal also considers that rather then improving, the human rights situation continues to deteriorate, and therefore calls on the conscience of European peoples, that they and their political representatives refrain from collaborating with the Colombian government. On the contrary, we urge them to take action to stop the violations committed in Colombia and to support the construction of a legitimately democratic society, through political negotiations and renewed institutions.

declaracion_english

declaracion_english