Monday, 14th January 2002

Getting on a plane from Britain, and within hours finding myself face to face with heavily armed Colombian riot police, shoulder to shoulder with workers and students locked in a struggle to keep public services in the public domain is, to say the least, a little bit disorientating.

Its hard to describe the feeling of being here with the people, in the middle of a heroic struggle, but I will do my best to paint a picture of the beauty of the merging of the individual into the collective mass of the class: flags waving, banners flying and hearts full of the conviction that to change our social reality we have to begin to think of others as ourselves, and to fight for common dreams.

Eighteen days into the occupation of CAM, the central administration Tower of EMCALI , in Cali (Colombia’s second city), and the surrounding areas have been transformed into a beehive of collective action aimed at feeding the body and the soul of the 800 workers inside, and presenting a message to the community at large that yes we have dignity, yes we can fight back, and yes we have an alternative that doesn’t necessitate that for my plate to be full, yours has to be empty.

Apart from the riot police surrounding the tower itself, the square surrounding CAM is in the hands of the people who patrol the perimeter 24 hours a day in workers teams, making sure that those who would seek to eliminate the dream of social justice, are at least for the moment, kept at a distance. On the right-hand side of the building is a huge make-shift kitchen feeding the hundreds of occupying workers inside with breakfast, lunch and dinner. A military style operation which moves from control, to production, to consumption, each with an importance that has been drastically changed due to the nature of the conflict.

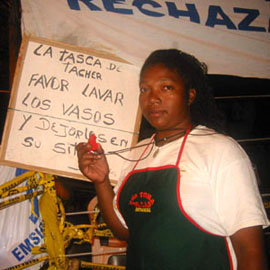

The perimeter of the kitchen is fenced off to prevent any unauthorized person from entering: Martha the cook has been renamed during the occupation and now is called Thatcher ¯ for the steely nature in which she organizes the troops, and prepares the food. “If somebody slipped in and poisoned the food the occupation would be over, and then where would we be?” But more than the security, she works with a passionate belief in the struggle. “I haven’t been home for 18 days, I work, live and sleep in this place. Last time when SINTRAEMCAL took the tower, the workers inside got fed up with beans and rice. I change the menu every day, and make sure it is keeping them happy”. Today’s lunch was a mixed rice with beef, sausages and ham, a salad, and a milk pudding dessert. “ I do it all with lots of love, even if they think I am a dictator they know that this job is important.”

Once the food is prepared it has to pass through a committee comprised of police, government authorities, and union representatives. The police check it all with a spoon making sure nothing but food enters, the union ensures that the police don’t poison it, and the government authorities attempt to make sure that neither side breaks the rules of the humanitarian agreement that was signed between the conflicting parties three days into the dispute and covers the entry of food and medicine into the building.

As the food moves on in its journey into the tower, Martha and the rest of her team take a break, tell some jokes, and she starts thinking about the next meal. After about an hour she calls the President of the Union, inside the occupation, to check that there was enough food, and that they enjoyed it. He normally tells her that it was terrible, and she knows by these comments that it was good. I feel proud to be with her.

Across the road from Martha’s kitchen is a makeshift stage where community leaders, activists, and sympathizers with the struggle, make their speeches, trying to keep up the spirits of those outside and inside the occupation, and explain the changing situation. On some days, there have been 20,000 supporters outside the tower, and every few days there is a big meeting with several thousand people. One was even beamed via video link to British trade unionists and Colombian exiles at the headquarters of the British TUC. “Our struggle needs to be international, because these policies of privatization are not just destroying our lives” said Arial, the regional Human Rights representative of the Central Workers union, the Colombian equivalent of the TUC.

Next to the stage, and all around the square, the walls are adorned with colorful union and social organization banners with slogans such as “SINTRAEMCALI is the union of the people, and the people will defend it”, “ Better to die for something then live for nothing”, and a whole range of other messages of support and solidarity.”

Directly in front of the building, lined up against the metal barriers put up by the police, families and friends gather and shout messages of support and news from home to those inside. I do the same, and wave to my comrades inside. The struggle is personal as well as political, and in a movement where fear of the death squads permeates everyday life, trust and friendship are everything.

I look around and try to think of ways to describe all this. The whole square has such a feeling of creativity to it, and of hope: that this time the downtrodden can win. As I link my arms up with others to block the roads, and shout messages of support to those inside, I too become locked again into the dream that we can do it, and resign myself to the fact that even if we can’t, that dream is worth fighting for.

Mario Novelli