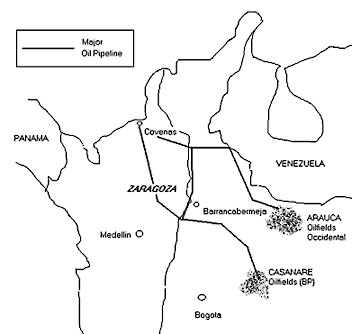

The first pipeline was built in 1990/91 by the state oil corporation Ecopetrol. It set up a special company ODC to run the project. The ODC pipeline is 480km long, starts in the central Magdalena valley, and ends at the Caribbean port of Coveñas.

The pipe was laid along the higher ground of undulating terrain, with the peasant plots directly below. ODC stripped all the trees from along the pipeline corridor, leaving it without vegetation, exposed to water and wind erosion. The earth moving operations caused avalanches, blocked springs and diverted streams. Works for the pipeline destroyed 150 water sources along the Zaragoza section alone. ODC’s restoration work was carried out badly, topsoil was not replaced, and sacks of earth had rotten away within a few months. Farm animals that ate the synthetic sacking were poisoned. The peasants lost their fruit trees and other crops.

In the early 1990s, getting its Casanare production to the Caribbean was a crucial challenge for BP. In December 1994 BP formed a new company called Oleoducto Central, S.A. (OCENSA), partnered by Ecopetrol, two Canadian companies, and the oil operators Total and Triton. OCENSA managed the construction of a 800 km pipeline which crosses the eastern Andes, before it meets up with the ODC line, running alongside it north to Coveñas.

BP got directly involved with communities along its new pipeline. David Arce Rojas, the agent of BP Exploration Company (Colombia), signed detailed eight page contracts with the peasant proprietors. The contracts agreed compensation for a strip of land just 12.5 metres wide. The compensation rate was 400 pesos (worth about 25p at the time) per square metre of this strip, plus any additional damages. Between June 1995 and March 1996 BP made three payments to each smallholder. In one typical case the peasant family’s total compensation package was for 1,576,250 pesos, about £1,000 or £4 per metre of pipeline at 1996 exchange rates.

The OCENSA line came on-stream in 1996, by which time the security situation had deteriorated in the Zaragoza region. Army units enforced a civilian free corridor for 100meters on either side of the double pipeline. The army brought in a 6pm to 6am curfew, which curtailed locals’ access to their own land, and for some to their homes. The combined effects of additional erosion from the second pipeline and the curfew meant that instead of losing use of a narrow corridor, the peasants had lost use of their entire holdings.

OCENSA now represents ODC’s interests as well as its own in the dispute with the peasants. The peasants have been forced to quit their homes and have fallen into acute poverty in the outskirts of Medellin. They have lost everything. The peasants sum up their predicament with the saying, "My shirt has no value to you, but for me it has".

Five families are still seeking compensation from ODC for damages and loss of income . A second group of twenty families has claims against OCENSA for damages caused by BP’s Cusiana pipeline. A third group of families from Segovia is also claiming.There is ample evidence. A report by two officials of the Zaragoza court summarises the damage as "constant erosion, scarce re-vegetation, and fundamentally the total lack of water".

OCENSA has so far refused to make a settlement beyond the original payment. Its spokesman claims that, "No company has had such environmental responsibility. We’ve done things well".