by Michael Gillard and Melissa Jones

Chilling Colombian police and court documents implicate BP, Britain’s biggest company, in the murder of an environmental regulator who was about to blow the whistle on corruption.

A paramilitary death squad in Eastern Colombia, where BP operates a massive oil field, assassinated Carlos Vargas in 1998. However, government investigators have gathered evidence alleging someone in BP’s controversial security department contracted out the hit to the death squad. They have also linked that death squad to the local army brigade set up to protect the oil company’s sprawling installations.

Now BP, which is close to the Blair government, is under pressure from dissident Labour MPs to honour its policy of "radical openness" and reveal the names of their security personnel in Colombia at the time of the murder.

So far it has not done so despite requests from the Colombian attorney general’s respected human right unit, which is handling the criminal investigation.

A lawyer for the Vargas family said he has been waiting two years to call the British and local security personnel to give evidence about the murder, as part of a two million dollar compensation claim against the Colombian government.

BP security in Colombia is trained and directed by the shadowy Anglo-American corporate mercenary firm, Defence Systems Limited. DSL has in the past repeatedly refused to co-operate with any Colombian government inquiry into its activities on behalf of BP.

Campaigners, some dressed as Colombian paramilitaries, raised Vargas’s murder during BP’s tumultuous annual general meeting in London last April.

BP chairman, Peter Sutherland, told shareholders in the Royal Festival Hall there was "no truth" in the "outrageous" allegations linking them to the killing. Chief executive, Lord Browne, had previously reassured the meeting that BP does not tolerate "bribery."

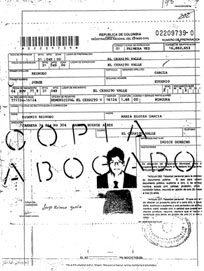

On 2 December 1998, two assassins on a white motorbike shot dead Carlos Vargas as he was being driven to his sister’s home for lunch in Yopal, the regional capital of Casanare. He was 49 and married with a daughter. The killers, who did not wear helmets, were identified by witnesses as they fled to a nearby safehouse where a third member of the death squad hid the motorbike. Vargas was elected director of the environmental regulator, Corporinoquia, in January 1998. He was not the establishment candidate and won by just one vote.

Vargas was responsible for a huge area of south-east Colombia dominated by BP and other oil companies. He awarded environmental licences, monitored compliance and, when necessary, imposed fines and shut down oil wells.

A report by the Colombian secret police, DAS, one week after Vargas’s murder, suggested he could have been killed by left-wing guerrillas, fighting a 38 year-old civil war, or even by his political enemies. But DAS appeared more convinced that the oil companies were behind the assassination.

The DAS report said Vargas was due to meet government officials in Bogota on 4th December to discuss non-payment of reparations for environmental damage caused by the oil companies. Court documents also reveal Vargas was about to go public with a dossier on corruption between local officials and oil companies, including BP, over the awarding of environmental licences.

The DAS report says Vargas’s enforcement of environmental regulations had cost oil companies millions of dollars. It claimed "the oil industry was interested in removing [the regulator] from his post" and "could have put a contract on him."

Vargas’s wife, Nelly, later testified to the Attorney General’s human rights unit that her husband had always refused to do "deals under the table" with the oil companies.

Four months before his murder, Vargas organised a filmed public meeting to oppose BP’s application to the Environment Ministry for one all- encompassing exploration licence which would bypass Corporinoquia’s oversight. Vargas was concerned about the reaction of the oil companies to his opposition, his official advisor, Alfredo Suarez, told the criminal investigation. Suarez said his boss believed these companies had financial links to paramilitaries operating in the oil region of Casanare. BP has always denied such links.

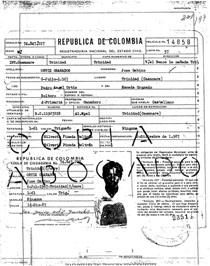

However, the most damaging evidence of a plot to kill Carlos Vargas comes from the wife of the third member of the death squad. She is called Dilia and her husband, Gabino Ortiz Granados, was the man who provided a safehouse in Yopal for the killers immediately after the hit. Dilia only spoke to a local police officer when Gabino was shot in the head just two months after Vargas. She believes her husband was killed because he knew too much about the plot. Dilia told the officer: "[Gabino] said to me a BP official spoke with commandante Chubazco, who at the time was head of the paramilitary in Casanare, and asked him to do a job. He was referring to getting rid of the director of Corporinoquia because he was going to revitalise a complaint about contamination or reforestation which would cost the [oil] company a lot of money." Today Dilia and the police officer that interviewed her are in hiding.

Gabino’s death was part of an extraordinary sequence of three murders, which effectively stymied the criminal investigation into Vargas’s assassination. Chubazco, the paramilitary leader, was assassinated ten days after Vargas. Two months later Gabino was dead.

In February 2000 police finally caught one of Vargas’s killers, a young paramilitary called Rodys Cuevas, but he was murdered in prison eight weeks later, before he could testify.

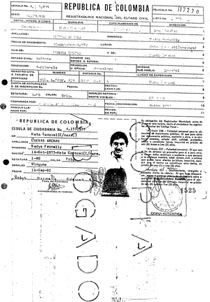

Both the assassins, Rodys Cuevas and Jorge Reinoso, who is still at large, plus two other local paramilitaries named in the criminal investigation were former members of the Colombian army’s 16th Brigade in Casanare.

This 5000-strong brigade was set up and is now indirectly funded by BP and its consortium partners – Total of France, US oil giant Triton and Ecopetrol, the Colombian state oil company – to protect installations and staff from leftwing guerrillas who regard BP as a military target. The rebels have killed and kidnapped its workers.

In April 2000, government investigators asked BP and two other oil companies to provide the names of its security personnel, including those who left the country soon after Vargas’s murder.

The other two oil companies – Occidental and Petrobras – complied immediately but BP refused. Instead it approached the Attorney General who assured them the request was legitimate.

At BP’s AGM in April, an irate Peter Sutherland told bemused shareholders that the company had offered the Attorney General "full co- operation" and dismissed the allegation of complicity in the murder as "ludicrous."

However a BP spokesman could not confirm that the names of its security personnel have now been provided, some two years after the oil giant was first asked by the murder inquiry.

This lack of co-operation contradicts BP’s much-vaunted commitment to "radical openness" outlined in their business policies.

The links between the death squad that killed Vargas and the 16th Brigade also undermine BP’s belief it can have military protection "free of human rights violations." Prior to the Vargas murder, two retired Colombian army officers working for BP security in Casanare had left because their past links to paramilitary death squads were exposed.

Nor is this the first time that the Attorney General’s human rights unit has investigated BP’s security arrangements in Colombia. BP’s security advisers, DSL, refused to co-operate over claims it had run "intelligence cells", brought in weapons and was secretly training the police in counter-insurgency tactics. Nevertheless BP renewed its lucrative contract.

At the AGM Peter Sutherland refused to answer one insistent campaigner who asked why BP would not terminate DSL’s contract. DSL is the type of firm that foreign secretary Jack Straw is considering regulating in the recent green paper on the use of private military

companies to replace British troops in conflict zones.

Two dissident Labour MPs, Dr Ian Gibson and Jeremy Corbyn, have written to Lord Browne expressing concern over BP’s activities in Colombia. Dr Gibson also met one of the environmental lawyers who helped Carlos Vargas develop his corruption dossier. The MP heard about four murders in 1997 of a campesino family who brought a legal action against BP for environmental contamination caused by gas flaring at the central processing facility. Gibson said he would raise these issues in the Commons.

The compensation claim by the Vargas family contains a chilling line which sums up the price paid by those who speak out in Colombia. It simply says:

"The death of Carlos Vargas was a death foretold one thousand times and the authorities were deaf and blind."

BP is not a defendant in the compensation claim but is named as a possible intellectual author. The family is claiming moral and material damages and just over half a million dollars for various local environmental programmes. They also want a public apology by the Colombian government.

The different security arms of the Colombian state directly named in the claim – the army and the police – are all key players in protecting the Colombian oil industry. BP has individual contracts with both these security forces. Family lawyer Eduardo Carreño said by eliminating the death squad members it is now almost impossible to discover who ordered Vargas’s death.

A spokeswoman for the Attorney General’s human rights unit said the criminal investigation is still open. But the government investigators who originally asked BP to comply with the names of its security personnel are now in exile. They received death threats after their legal pursuit of the notorious ‘Butcher of Uraba’ General Rito Alejo Del Rio, whose links to paramilitary groups in Colombia’s dirty war are well-documented.

An edited version of this article appeared in the Sunday Times on 21st April 2002.